Why Natural Fibers Outperform Synthetic Gear

Introduction

Natural fiber outdoor clothing offers superior breathability, moisture regulation, and comfort compared with synthetic gear. Unlike synthetic materials that can trap moisture and heat, natural fibers like wool work with the body’s physiology. This supports thermo-regulation and creates a healthier micro-climate next to the skin. This alignment makes natural fiber clothing foundational for rewilding practices, including Forest Bathing, barefoot walking, and mindful outdoor immersion. This article examines the personal transition from synthetic gear to natural fibers. It also delves into the science supporting the importance of this change.

Have you ever woken up to a cold, rainy morning and just wanted to crawl back into bed?

When I discovered the power of wool hiking clothes and waxed cotton jackets, my perspective on “bad” weather changed completely.

Damp, windy, bone-chilling days are no longer something to avoid—they’re a call to rise to the challenge. I’ve become obsessed with testing natural performance gear to see what it can do, pushing it to the edge. Why did outdoor clothing and gear become ubiquitously synthetic? I have been on a journey of rediscovering natural fibers and inventing and designing gear which can outperform synthetic counterparts. Join me on this in depth series as I explain my process as well as the science and practical application of my natural fiber outdoor wardrobe that rocks!

The Superpower of Wool: Heat of Adsorption

Wool has a special ability to manage moisture in a way that makes it ideal for outdoor clothing. Here’s what happens:

- Adsorbing Moisture Releases Heat: Wool fibers naturally adsorb water vapor from your body or the air. Adsorption means that water molecules get trapped in the naturally porous fibers of the fabric versus absorption where water molecules permeate the fabric and are wet to the touch. For wool, because the water is trapped, it doesn’t feel wet to the touch. As this moisture enters the fibers, a small amount of heat is released. This is known as the heat of adsorption, and it’s why wool feels warm, even when it’s damp.

- Keeps You Warm in Wet Conditions: This ability to trap heat while managing moisture makes wool perfect for cold, wet environments. If you’re caught in the rain or snow, wool doesn’t lose its insulating power the way many other fabrics do.

- Regulates Your Temperature: Wool adapts to your body’s needs. In cold weather, it traps heat, keeping you warm. In milder conditions, wool pulls moisture away from your skin and helps prevent overheating, creating a balanced and comfortable experience.

This makes wool an all-around excellent choice for outdoor clothing, where moisture and temperature can fluctuate.

How Synthetic Clothing Handles Moisture and Warmth

Synthetic fabrics like polyester, nylon, or polypropylene are engineered to handle moisture in a completely different way. Here’s what sets them apart:

- Repelling Rather Than Absorbing Moisture: Unlike wool, synthetic fibers don’t absorb moisture into their structure. Instead, they are designed to wick sweat away from your skin to the fabric’s surface, where it evaporates.

- Synthetic materials such as pile jackets or synthetic or down filled sleeping bags sewn with synthetic fabric, do not dry from the body heat while wearing. The only way to dry these is in the air or with a fire. This can be a problem during wet conditions where sometimes neither options are available.

- No Heat from Absorption: Since synthetic fabrics don’t absorb water vapor, they don’t release heat when they get damp. If synthetic clothing gets wet (like in a rainstorm), it can often feel cold and uncomfortable because water gets trapped between the fabric and your skin.

- With synthetic fabrics the sweat does not leave through the fibers, but rather in between the weave of the fibers. This makes the process of evaporation inefficient because some moisture is always trapped next to the skin.

Wool can be considered an ‘active’ fiber due to its ability to absorb and desorb moisture vapour as conditions around it change.

Water vapor molecules absorbed by wool attach to specific chemical sites within the structure, losing some of their energy as heat. Thus moisture absorption by wool as humidity rises increases the fiber temperature, and moisture release following a decrease in humidity lowers it. The amount of heat involved is significant. A kilogram of dry wool placed in an atmosphere of air saturated with moisture releases about the same amount of heat as that given off by an electric blanket running for eight hours. In the Lucky Sheep Rewilder20 Wool Sleeping Bag, there are about two pounds of wool batting insulation. This is the equivalent of the amount needed to release heat for eight hours.

Also, inside the wool sleeping bag, the camper can add their own moisture by breathing inside the bag. That means, pulling the top over the head, and breathing the warm air inside the bag. The moisture in the breath will be adsorbed into the wool fibers and migrate to the outside where it will be released. This cannot be done inside a synthetic or down-filled sleeping bag where it would actually make the camper colder by holding the moisture inside, but is unique to wool alone.

Wool can be used in based layers as well as insulation layers. Some types of wool even shed water thus acting as a shell layer. Where wool isn’t the best choice is a wind shell. That is where beeswaxed canvas or oilcloth comes in. See Part Three for how to handle the wind/rain shell.

During a rainy hike, a wool garment will shed the rain (liquid water), but adsorb internally the water vapor generated by the body in response to the effort of hiking. The exact degree to which this works depends on the type of wool fabric. Some wool fabric is made for this type of action.

Key Differences Between Wool and Synthetic Clothing for Outdoor Use

Let’s compare wool and synthetic clothing side by side to highlight their advantages and disadvantages in outdoor conditions:

Warmth When Wet

- Wool: Stays warm even when damp, thanks to the heat released during moisture absorption.

- Synthetic: Loses its insulating ability and can feel cold and clammy when wet.

Moisture Management

- Wool: Adsorbs moisture into its fibers, managing it slowly while keeping you comfortable.

- You can wear wool even when wet as it will still keep you warm and will slowly dry out from your body heat.

- Synthetic: Wicks moisture away from your skin quickly but doesn’t retain warmth. Keeps some moisture next to the skin.

Drying Time

- Synthetics fabrics such as polypropylene and poly fleece won’t actually absorb much water, but will be wet and hold the water against you, where it will rob you of heat

- Cotton and other plant material absorbs all the water it can … immediately … (unless the cotton is treated with wax)

- Wool adsorbs a lot of water … slowly, and internally … however the wool still insulates the wearer.

Warmth to Weight Ratio

Many claim wool doesn’t work because it has a lower warmth-to-weight ratio than synthetics and down. However, this only applies under IDEAL conditions. That means, dry conditions. And in effect this only applies when thought of as a static insulation. In reality, where there is exertion, rain, mist, and changing conditions, including wind and exertion level, the synthetic counterparts do not outperform the wool.

Physical exertion, even on a cold day, causes the body to produce warm water vapor. Wool will adsorb the warm vapor, trapping the moisture and the heat inside the fibers. Wool can keep the rain from reaching you, while at the same time grabbing the perspiration vapor and heat. When you hike hard in synthetic rain you will just get soaked from the inside, even in the clothing that claims to breathe. This is one of the conditions where the wool wins on the warm-to-weight ratio.

Conclusion: Wool’s Heat of Adsorption Makes It a Winner for Outdoor Adventures

In 1858, French Scientist Coulier was the first to observe that when dry wool was moved to a humid room – when it adsorbed water — it produced heat … the small amounts of energy known as the “heat of sorption”. You can notice this in real life when going out on a cold, humid day. Your woolen outerwear will prevent the humidity of the air from chilling you … the wool will dry the air near your body, creating a lower-humidity, warm micro-environment. Wet (high humidity) air pulls heat from the body much more quickly than dry air.

The process of internal adsorption is very gradual, and is relatively impervious to liquid water. This is important in cold weather, where heat and energy must be conserved. Physical exertion, even on a cold day, causes the body to produce warm water vapor. Wool will adsorb the warm vapor, trapping the moisture and the heat inside the fibers. Wool does this even on a cold, rainy day!

Wool’s unique heat of adsorption gives it a significant edge when it comes to outdoor clothing in cold or wet conditions. Its ability to release heat when absorbing moisture helps you stay warm and comfortable, even in the harshest environments.

Rewilding Adventures Start with Bad Weather

Pushing the body up against the elements is at the heart of rewilding adventure. Bad weather is the ultimate test of our primal nature and skills. Anyone can hike when the sun is shining. True independence comes when you know you can take on anything Mother Nature throws at you.

My Early Forest Bathing Retreats and the Quest for Natural Fibers

Several years ago, I began a deliberate transition toward an all-natural outdoor wardrobe. At the time, my indoor environment was becoming completely free of plastics and synthetic materials—clothing, bedding, and furniture—aiming to create a healthier, low-toxicity living space. It felt contradictory that while my living space was moving toward the natural, my outdoor gear remained dominated by plastics and synthetics.

I noticed an immediate, embodied difference when I wore wool instead of synthetic fleece: I felt more alive, energized, and connected to my surroundings. That intuition propelled me into questioning the modern outdoor gear paradigm. What was this thing called natural fiber, and why did it feel so different?

As a lifelong outdoor guy I had gone along with the trends like everyone else, believing synthetics offered better performance and less weight. The big buzz word “moisture wicking” was always used to kill any idea we should use natural fibers. Slowly my wool sweaters and socks were replaced with pile and polypropylene. There was a period you couldn’t find anything natural in an outdoor gear shop.

My hypothesis—initially anecdotal—was later reinforced by scientific research showing that wool’s natural structure provides dynamic breathability and moisture buffering unmatched by most synthetic fibers. In controlled tests, traditional performance fibers like merino wool demonstrated superior regulation of the next–to–skin microclimate, maintaining thermal comfort across both activity and rest phases significantly better than polyester and other synthetics. (wool.com)

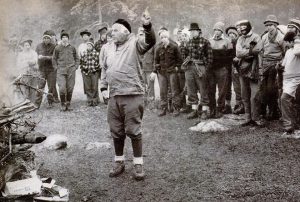

A Personal Connection to Traditional Outdoor Education

My early formation as an outdoor leader came under Paul Petzholdt, founder of the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) and the Wilderness Education Association (WEA). Petzholdt emphasized wool long before synthetic fabrics dominated the market. He taught with cotton windbreakers and wool sweaters—materials now largely absent from mainstream outdoor shops—and warned students about the limitations of down and moisture-trapping synthetics long before moisture-wicking became industry dogma.

In 1983, during a six-week WEA leadership expedition in the Nantahala National Forest, Paul gifted me some wool base layers—a formative experience that would later influence my gear experimentation decades later.

The Rise of Synthetics and the Revival of Wool

The outdoor gear industry experienced a synthetic boom starting in the late 20th century. Plastic-based fibers like polyester and nylon became the basis of performance claims including moisture wicking and lightweight warmth. Over time, wool nearly vanished from outdoor retail shelves.

Later, a revival occurred, led by brands like Smartwool and Icebreaker, promoting merino wool as a modern outdoor fabric. Merino, a specific sheep breed with fine fibers, is less itchy and highly versatile as base layers, socks, and sweaters. Scientific testing has since demonstrated merino wool’s superior capacity to manage moisture and regulate temperature, significantly outperforming synthetics in maintaining comfort across weather conditions. (wool.com)

Early Experiments: DIY Natural Clothing Systems

At the time, I just wanted to feel good. All I knew was wearing wool vs. synthetic pile made me feel immediately more alive and energized. It was almost like trying to find the Holy Grail. What was this mysterious thing called NATURAL FIBER? What I would later find with research, my hypothesis was completely validated with science. Essentially, we breath through our skin. Synthetics block that process. Synthetics also rob electrons from our body and short circuit the electrical flow along our skin called Peizo Electricity. What is Forest Bathing if we aren’t able to absorb the negative ions from the air and synch our brains with the Shumann’s Resonance?

Around 2010, natural fiber outdoor wear was still difficult to find. I scavenged thrift stores. I DIY patched together a wool-centric system. While cotton windbreakers and pants were makeshift, the wool base and insulation layers delivered a distinct physiological experience. Wool’s ability to absorb and release moisture vapor—up to approximately 35% of its own weight without feeling wet—creates a dryer and more comfortable microclimate next to skin than typical polyester or nylon layers. (International Wool Textile Organisation)

I also built experimental natural fiber gear—backpacks, tents, and sleeping bags—testing how my body responded to real weather conditions. I wasn’t concerned with appearance or fashion; I was rediscovering embodied comfort and connection to the environment directly.

Outdoor Clothing Basics: The Three-Layer System

(Adapted for Natural Fibers)

Through field testing in the Southern Appalachians, I refined a natural fiber clothing system that supports comfort across seasons:

1. Base Layer

The base layer must be:

- Thin and stretchable

- Moisture managing

- Close-fitting to prevent cold air pockets

Wool base layers excel because they not only wick moisture away from the skin but release vapor into the air with minimal clamminess, enhancing breathability. (International Wool Textile Organisation)

2. Insulation Layer

Historically wool served as the primary insulation, replaced later by synthetic fleece and down. Wool offers robust insulation because its natural crimp traps air, creating pockets of warmth while still allowing vapor to escape. (Woolmark)

3. Windbreaker / Outer Layer

A wind and rain shell must block wind chill without trapping heat and moisture. Before synthetic dominance, tightly woven cotton treated with beeswax or oilcloth served this function. Today, wool pants and overshirts offer superior moisture regulation and breathability compared with most all-synthetic outer layers, especially when paired with lightweight protective shells.

Natural Fiber vs. Synthetic: Moisture Wicking and Breathability

Understanding the difference between moisture wicking and breathability is essential:

- Moisture wicking describes how a fabric moves liquid away from the skin.

- Breathability refers to a fabric’s capacity to allow moisture vapor to pass through the material itself.

Synthetic fabrics wick moisture via pores between fibers but do not allow moisture to move through the fiber itself. This traps humidity next to the body. In contrast, wool’s fiber structure allows moisture vapor to pass through the fiber, enhancing comfort and thermoregulation. (International Wool Textile Organisation) This process is known as heat of adsorption. Understand this better from The Superpower of Wool: Heat of Adsorption.

Wool’s natural properties regulate heat and moisture without mechanical or chemical additives, which contributes to a more stable thermal environment next to the skin—especially in changing conditions. (wool.com)

Why This Matters for Forest Bathing and Rewilding

Forest Bathing and rewilding practices involve deep sensory engagement with the environment. If clothing inhibits breathability or traps moisture, it can interfere with the body’s natural thermoregulation and sensory perception. Natural fibers like wool optimize the body’s biology for a more integrated experience of the outdoors.

Conclusion

Moving from synthetic to natural fiber outdoor clothing was, for me, a shift from gear that dominates the body toward gear that supports the body’s innate regulatory mechanisms. Wool’s inherent breathability, moisture management, and dynamic thermo-regulation make it uniquely suited for outdoor adventures and rewilding practices. While synthetics have their place in modern gear systems, natural fibers restore a fundamental connection between the body and the environment—one that modern outdoor culture often overlooks.

My journey led me to develop natural fiber outdoor clothing and gear as well as write a book. I break down my system and process in detail in my book: A Rewilder’s Guide to Outdoor Adventure